|

Stephen

Barber & Sandi Harris, Lutemakers |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Catalogue and Price List 2017 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Catalogue 2017 Welcome to the recently-updated Catalogue and essential information page of our website; we hope that you find looking around the site to be interesting, helpful and informative, and we'll be pleased to hear from you. We've added new images and texts throughout the site during the recent update. Business Facebook Page: Neither of us has a personal Facebook page, however, we launched a Business Facebook page in early September 2014, and we've since been regularly adding images and descriptions of current and new work, as well as images of work in progress, us working and short movies, which people have often requested: www.Facebook.com/BarberAndHarris There are already links to short movies that have been made about our workshop, and the Yards where we work in general. The Facebook page will complement our main website page, and we will be able to keep it regularly updated, fresh and interesting. Instagram Page: You can now follow us on Instagram: @barberandharrislutes Two of Santa's Elves, who do the the real work. Now trending . . . We wrote here previously about the devastating fire that struck our workshop in June 2014; we'd like to reassure you that we are still in business and operating, albeit at a slower pace than before; here's a brief account of how things have panned out and evolved: In the aftermath of the fire, we were grateful to have received many messages and offers of help, as well as very practical assistance in clearing-up and making-good, from several friends and colleagues, among whom we'd particularly like to thank Lynda Sayce, the well-known theorbo player, expert and scholar, who interrupted a busy work schedule – twice – to spend time helping us here; and also Patrick van der Valk, who drove over from Utrecht to spend a long weekend helping us; he's now an expert in cleaning metal tools corroded by fire extinguisher chemicals, as well as being a computer systems expert. After the best part of six months unable to work properly, we were finally able to get going again. It appears, however, to be the case that several people have wondered if we'd ceased working, or closed-down in the aftermath of the fire; the website having not been updated since March 2016 seems to have added to speculation. What actually happened, according to medical opinion based on numerous tests and evaluations including MRI and CT scans, is that as a result of fighting the fire, surrounded by dense black smoke (the nearby windows couldn't be seen a metre away on a bright sunny day), Steve seems to have inhaled various toxins, which may have caused a severe ongoing balance problem; and a diagnosis of PTSD – triggered by the extreme experience and trauma of 'fight-or-flight' where defeating the furiously-burning fire was concerned . So we had to 're-boot', taking Steve's changed health situation into account. We decided to concentrate on getting up-and-running again, while we worked out how best Steve could adapt, and develop new approaches and methods, given his current ongoing health condition; we're working more slowly, but every instrument we've made since we got started again has been as good as anything we ever made before the fire, and all have been very well-received, from Portland, Oregon to Chattanooga, Tennessee and from Antwerp to Cambridge. You can order with complete confidence, as before. Please read on; we hope you enjoy browsing through our site. Last updated on Monday 7th August 2017 Please note that the prices shown throughout this website are current for 2017, although we reserve the right to revise them at any time.

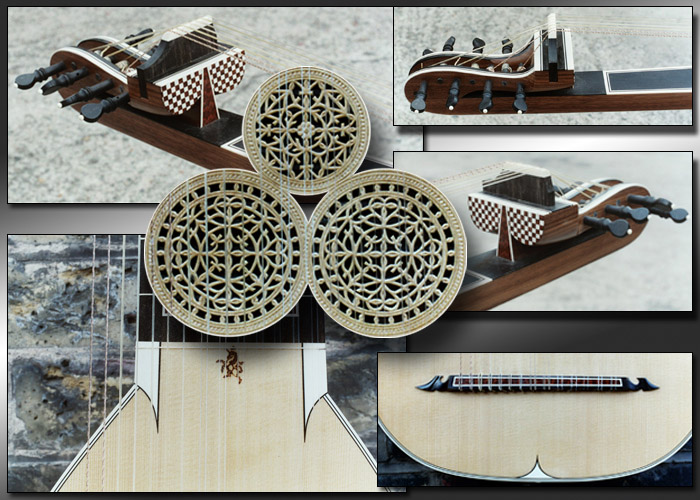

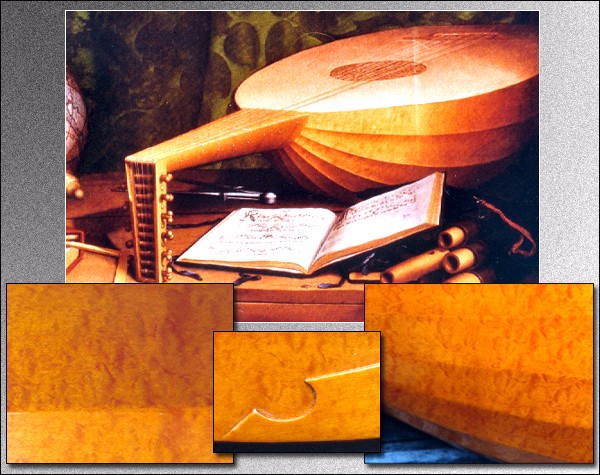

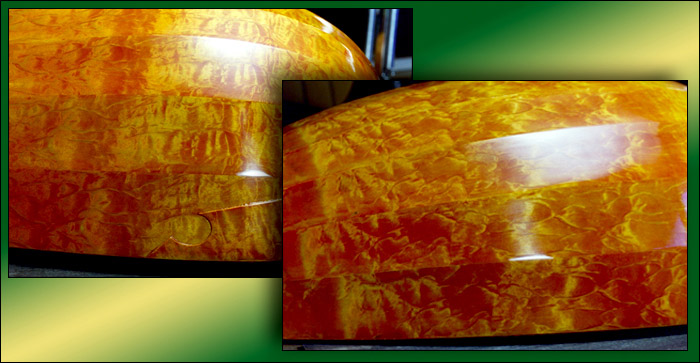

Thirteen-course baroque lute after Sebastian Schelle, 1744; birds-eye maple striped with plum, colour-vanished (amber-based oil varnish); the rose design used here is from the 1726 Schelle lute in the Yale collection, New Haven, Boston. (No. 1 in the Thirteen-course lutes section) The image above dates back to the early days of our website – founded more than thirteen years ago in May 1998 – and we have placed it here again following requests to do so. The lute was bought from the "for sale" section of the site by a customer in Japan in June 1998; he went on to order three more instruments. By way of comparison, the image below is of a more recent instrument, made for a player in Buenos Aires:

Above, images of a 7-course Renaissance lute made in October 2009. The instrument above is a seven-course renaissance lute, based on an anonymous early 16th Century original, labelled 'in Padov 1595'. This instrument has been built in a late sixteenth Century style; its nine-rib back is made from two types of Hungarian ash, in a striped arrangement, colour-vanished (with our own amber-based oil varnish). The rose design used here is from an instrument in the Vienna Kunsthistorischesmuseum collection, C33, labelled 'Hans Frei (the design chosen by the player). The neck and pegbox are ebony-veneered, the fingerboard is ebony, as are the pegs. This lute was made for Rolando Ossowski, of Buenos Aires, in late October 2009. Rolando sent us this message, written on a Christmas card: Thank you for making me an instrument so beautiful and true. Thank you for all the hard work and the love you put into it. It flew from London to Washington very comfortably and calmly, at the back of the Business Class section! Now for the second leg of its long journey, to Buenos Aires. As soon as I'm able to go back to London, I'll ask if I can visit you for a cuppa. In the meantime, all the best. R. Another 7-course version of this lute – made using design cues from the early 16th Century – was sent on March 1st to Jean Paul Tran, a lutenist in Grasse, France, who wrote after receiving it: "Dear Sandi and Stephen, after picking up the lute at my father's house, I spent the evening tuning and playing this wonderful instrument. It is well-balanced and easy to play. The timbre is delightful. I love the chanterelle, so easy to play. This lute is the perfect size for me, it fits me in every aspect. I really love its early 16th Century design. The fingerboard, soundboard and rosace are 'magnifiques', as we say in French. Thank you so much for this wonderful lute. Kindest regards, Jean Paul Tran". (Please also see No. 11 in the Six-course lutes section). .Introduction Our website was launched nearly 20 years ago, in May 1998, when it originally consisted of just a 'Gallery' page and a 'For Sale' page. We've expanded the format over the years to not only include descriptions of instruments that we are currently offering (along with a lot of supplementary information about the original instruments) but we also post here material which we think is relevant to the process of lutemaking, and which gives it a wider context, as well as other ancillary information – for example, about the exhibitions we attend during the year. The Catalogue pages of this website contain brief descriptions of instruments which we are currently offering, many of which are illustrated with colour images. All of the instruments offered herein are based on our own extensive research and documentation; this aspect of our work involves visiting collections throughout Europe on a regular basis, thereby keeping abreast of the latest discoveries, and developments in research. A recent aspect of this approach was our being asked to examine and verify an important lute by Laux Maler which had appeared in early 2004. Its soundboard being off, we of course extensively photographed and measured it. Similar work in this area in recent years included days of intensive research spent in Vienna and Nürnberg in January 2002, where we examined in considerable detail the KHM Georg Gerle 6-course lute, and two days later the GNM Laux Maler lute (originally probably also a 6-course) in order to refresh, update and expand our existing information on these two wonderful instruments. Further visits were made to these and other German and Austrian museums during 2004 and 2005; earlier in 2004 (just after returning to London, having in late January photographed and measured the 1734 Johannes Jauck triple-pegbox, 13-course baroque lute in the KHM, Vienna) we were asked to examine and give an opinion on the soundboard of a recently discovered Laux Maler lute which had surfaced; this very interesting instrument – probably built on the same mould as the Nürnberg Maler – has the best-preserved soundboard of all the Malers. A complete survey of its thicknesses and bar placement was made, and a simultaneous dendrochronological examination revealed that the youngest year-ring was dated to 1529, thus falling well within Maler's working lifetime. We have completely measured and photographed this new discovery, having travelled overseas in late May 2004 to document and measure its body (its soundboard had been removed from its body and sent to London separately, for our opinion and a dendrochronological examination by John Topham, the noted expert in this field). To complete this Maler 'cycle', in June 2004 we measured the two instruments in the Lobkowicz Collections, at the Nelahozeves Castle, Czech Republic. Having thus examined all of the five known Maler lutes, we have observed clear relationships between them: the recently-discovered instrument is virtually identical to the Nürnberg instrument (and they have identical roses) and these two and one of the Lobkowicz lutes are made from Hungarian ash, a highly-figured and very hard type of ash, found mostly in eastern Europe; they all have 9-rib backs. The London V&A instrument and the other Lobkowicz example are similar in geometry (although the V&A instrument is the largest of them all) and they both have 11-rib backs, and are both made of lightly-figured maple. None of the five Maler lutes have fillets between their ribs. At the suggestion of Joël Dugot, an article is planned on the surviving Maler lutes in the near future. Guitars are not overlooked: another interesting measuring trip was to the Brussels MIM (Musical Instrument Museum) on August 5th 2002, to examine the Cassas, Baña baroque guitar, a beautiful, intact example of Catalan 17th Century guitar making; we were also fortunate to be granted access to some interesting instruments in private collections in the Spring and Autumn of 2003, and again in 2005 and 2006. We're currently working on our first version of the 1680 guitar by Antonio Mariani (Leipzig 536) which we measured in 2004, and on orders for the 13c baroque triple-pegbox lute, based upon the 1734 Johannes Jauck lute (GdM 61) in the Kunsthistorischesmuseum, Vienna. Further measuring trips to the Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nürnberg have taken place in recent years – in November 2005 and January 2006 – when we measured and photographed guitar rosettes, and again examined the ebony-backed Sebastian Schelle 13 course baroque lute, MIR902, and noticed a few very interesting details we hadn't observed before (see the entry under No.3 in Catalogue 7). We returned there again in November 2007 to photograph the Laux Maler lute and re-examine its barring. Our ongoing and widespread research has included documentary technical drawings commissioned from Stephen by leading museums and private collections. Documentation and measurement has continued apace into 2012. We also regularly advise on and undertake conservation work, for both public and private collections. This depth of knowledge and experience is naturally reflected in the range and quality of the instruments described herein. The composite image below shows details of a chitarrone we built in 2004, based on an original made by Christoph Koch in Venice in 1650:

This instrument's triple rosette is closely based upon the Koch original; the fingerboard points and curved triangular inlay in the lower soundboard are mammoth ivory edged with a fine ebony line, the sides of the upper neck are veneered with walnut, and the upper pegox itself is made of walnut. The chequerboard pattern on the front of the upper pegbox is made from snakewood and bone squares. The black-stained bridge is surmounted by an inlaid panel of snakewood edged with bone and ebony; the 15-rib back of this instrument is made from ebony striped with ghostly-white holly staves. This is a 'fully decorated' version of this particular model: the triple white/black/white edgings to the upper neck are here applied not only to the front – which we usually offer as 'standard' – but also to the rear of the upper neck, and sweep around the curves of the upper pegbox. The instrument has double stringing on the fingerboard and single diapasons (as the original has) with a 7x2 / 7x1 disposition, at 860mm stopped string length, tuned to a (at 415). Stephen has been making lutes, vihuelas, early guitars and related instruments since 1972, and Sandi since 1983. We have worked together since 1986, and during this period we have built instruments for leading players and ensembles throughout Europe, the Americas, Australia and Japan. We regularly act as advisors and consultants to other luthiers, and Stephen has taught and trained many of the makers working today in Europe and the Americas through his earlier teaching work, including some who have themselves been teaching others (including, for example, Martin Haycock, who until recently had been, since 1984, teaching lutemaking at West Dean College, England; many subsequent students, for example Alexander Batov and Oliver Wadsworth, clearly benefited from being in the workshop with Martin, Stephen's former student). The German lutemaker Hendrik Hasenfuss was also heavily influenced by Stephen and Sandi's style of lutemaking. Stephen's knowledge, experience and methods have helped successive generations of makers get started. In addition to this teaching, other luthiers have been helped by the considerable number of drawings and articles that Stephen has published, and lectures, seminars and demonstrations we have both given. Broadcasts, recordings & performance Our instruments enjoy worldwide use in concerts, radio and television broadcasts, and on numerous CD and other recordings. They have been ordered by many distinguished players, including: Sven Åberg – Ariel Abramovich – Ron Andrico – Mitsuru Ayatani – Paul Beier – Thomas Binckley – Jim Bisgood – Gary Boye – Julian Bream – Bruce Brogdon – Elizabeth C.D. Brown – Jürgen de Bruin – Victor Anand Coelho – Antonio Corona-Alcalde – Andrea Damiani – Beate Dittmann – Martin Eastwell – Christoph Eglhuber – Wezi (Ben) Elliott – Kasia Elsner – Charles Edouard Fantin – Mike Fentross – Eugène Ferré – Tom Finucane – Dirk Freymuth – Christine Gabrielle – Negin Habibi – Lucas Harris – Vanessa Heinisch – Jacob Herringman – Scott Horton Robin Jeffrey – Edin Karamazov – Leif Karlsson – Hans-Michael Koch – Richard Labschütz – Esteban La Rotta – Jakob Lindberg Rolf Lislevand – Andrew Maginley – Wim Maeseele – Mark Mancina – Markus Märkl – Holger Marschal – Will Mason – Hållbus Totte Mattsson – David Miller – Pascal Monteilhet Michiel Niessen – Nigel North – Paul O'Dette – David van Ooijen – Franco Pavan – Radamés Paz – Barrington Pheloung – Pierre Pitzl – Eligio Luis Quinteiro – Keith Richards – Sigrun Richter – Kenji Sano Jordi Savall – Lynda Sayce – Andrea Sechi – Paul Shipper – Stephen Stubbs – David Tayler – Francesca Torelli – Taco Walstra – William Waters – Arto Wikla – Christopher Wilson and numerous other leading players worldwide. They can be heard on recordings by, amongst others: Tragicomedia – The Dowland Consort – The Lute Group – Hedningarna – Boston Baroque The Sixteen – Hespèrion XX – Circa 1500 – New London Consort – The English Concert The Academy of Ancient Music – L'Ayre Español – Les Arts Florissant – English Baroque Soloists – Le Concert des Nations The Kings Consort – The Harp Consort – Concerto Palatino – Les Trésors d'Orphée – Teatro Lirico Ensemble Kapsberger – La Capella Reial de Catalunya – Il Fondamento – La Venexiana – I Fagiolini – Zefiro Torna Exhibitions, conferences & seminars We travel across continental Europe several times during the course of a year, attending exhibitions and conferences, delivering instruments and buying wood, visiting clients, music colleges, courses, stages, festivals and expanding our archive of information on original instruments by visiting museums as an integral part of these trips. We are also in demand as speakers and participants at conferences and music festivals where the lute, vihuela and/or early guitar are featured; for example, in December 2002, Stephen travelled to Mexico City, at the invitation of Antonio Corona-Alcalde, to speak about the Chambure vihuela at the International Symposium on Musical Acoustics (ISMA). Another vital part of our work is regularly examining and documenting historical instruments in private and public collections, thereby keeping up to date with new discoveries, research and developments and expanding our archive of information on the originals of the instruments we build; several research visits are planned this year. The exhibitions and festivals that we attend regularly are in Regensburg and Utrecht, as well as others to which we are invited – such as the December 2002 ISMA conference in Mexico City. We used to attend the events in Bremen, Brugge, Herne, Innsbruck and Urbino, but do not do so these days because we usually simply don't have the time. In 2010 we unfortunately had to turn down an invitation to speak at the Deutsche Lauten Gesselschaft conference in Füssen, on the subject of Maler and Frei and the northern Italian lutemakers of the 16th Century, because of a prior engagement. We do still travel regularly across Europe buying timber, and are thus able to keep in regular personal contact with our clients across Europe – as well as in Australia, Japan and the Americas – and receive feedback on new instruments and models in the process of development. Players are always welcome to visit us at exhibitions, where we always have an interesting selection of new and recently-made instruments to try out – some of which will be for sale – and we welcome feedback and comment, as well as the opportunity to meet customers, renew old friendships and make new ones.

Waiting time / Availability – and reserved 'gaps' (August 7th 2017) Our waiting-list currently extends to around 14 months, October / November 2018; however, we deliberately reserve regular 'gaps' in the list in order to accomodate the player who requires an instrument urgently. Not running a 'continuous' list also of course allows us the flexibility to produce new models and prototypes, to travel for research and exhibition purposes, and to build instruments which are ready for immediate purchase: Instruments available for sale now We always have a selection of finished instruments in our workshop for players to try, some of which are for sale, and listed on this page of the website. Moreover, we are professional, full-time instrument makers, who enjoy our work immensely and work very efficiently, so that we are usually able to find a 'gap' within, say, the next 6 months at any given point, should your requirements mean that your need for an instrument is urgent. Please inquire for up-to-date details and availability of these 'gaps'. We also strive to fit in orders for Student Lutes between 8–16 weeks of ordering, since these instruments are ordered by students, young players or beginners, and we feel that it is vitally important – not least for the ongoing longevity of the current lute revival – that on the one hand, new enthusiasm is not frustrated by being pushed to the end of a waiting-list which may appear frustratingly-long to some – and on the other hand, instruments of an known, excellent quality are available for the beginner, so that he or she does not have to negotiate the often murky waters of the secondhand market. Location Our workshop is situated in central London, with private and secure vehicle parking available (and we're just outside of the Central London congestion charging zone ). We are about twenty minutes' journey-time on the Underground (Metro) from the Eurostar Terminal at Kings Cross / St Pancras station, with the nearest Underground station, Kennington, one stop from Waterloo and an easy 10-minute walk from Peacock Yard. Road and rail connections with Heathrow, Gatwick, London City Airport and Stansted are simple, and the A2 / M2 and M20 roads from Dover, Ramsgate and the Eurotunnel Terminal in Folkestone finish 200 metres away. Heathrow, Gatwick and Stansted airports are approximately 45 minutes away by train, coach or car, and of course London City Airport, convenient for flights from nearby cities such as Amsterdam, Brussels, Dublin, Edinburgh and Paris is close by, a short drive across the city from us; Victoria Coach Station is a short 15 minute journey away. String spacings, decoration & pitch Once a suitable model has been selected, choice of materials and style and level of decoration is always discussed with the player, and important personal requirements concerning left and right-hand string spacings, neck profile and thickness and action are taken into consideration, as well as stringing preferences. Please advise us of your preferences when ordering, we are happy to work with you to produce an instrument which incorporates your chosen left and right-hand string spacings, and any special requirements regarding neck profile, width and thickness. We understand that when a person orders an instrument, he or she will want it to be built so that it is immediately familiar and comfortable to hold and play; we always respond to and follow a player's requirements and wishes in this regard. Instruments not included in our Catalogue pages are also accepted as commissions; our ongoing research and travelling means that the list of instruments available will be regularly revised and supplemented. We also make a range of Student Lutes in 6, 7 and 8 course versions; production of these is limited to around 6 instruments per annum. All string lengths and other dimensions quoted are in millimetres. Pitch is assumed to be a'=440 Hz, or a'=415 Hz where specified; other pitch conventions can be worked to, please enquire. Left-handed instruments Left-handed versions of all of the instruments described in the Catalogue pages can be ordered at no extra cost. Over the years, we've made everything from a left-handed orpharion through to an archlute; although certain instruments present particular technical challenges (such as the 13-course bass-rider lute shown below) and therefore can take more time than a right-handed instrument, we don't charge extra.

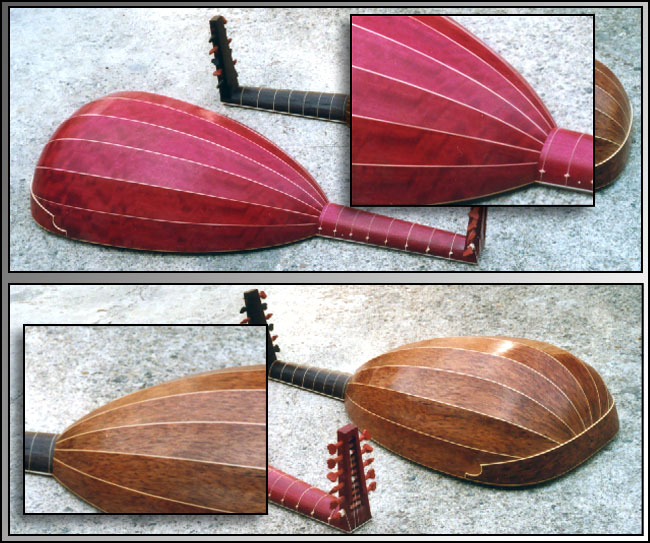

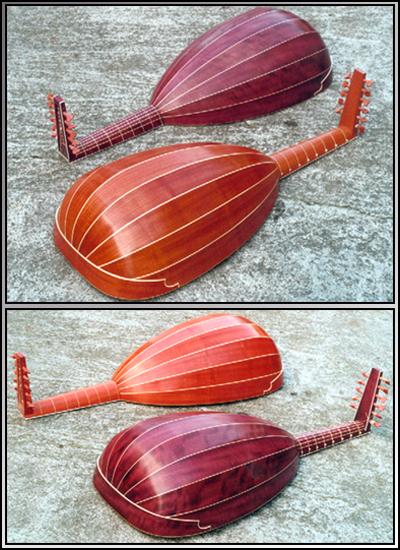

Shown above are two 13-course bass-rider baroque lutes – one right-handed, the other left-handed; they are both built to the same design (after an original by Sebastian Schelle, 1744). In the image above left, the instrument laying face-down is left-handed, and in the image on the right, the left-handed version – made in July 2004 – is on the right.

The images above are of a left-handed archlute we made in January 2006 for David van Ooijen, the lutenist and continuo specialist based in Den Haag. The instrument – which has a 15-rib yew heartwood back – was fitted with Dan Larsen's 'Gamut' gut strings. Dan's strings worked extremely well, and stayed in tune from when they were first fitted. Materials, construction & techniques The timbers and other materials we use, for both construction and decoration, are carefully selected to be as close as possible to those used on the original instruments; we don't use ivory for nuts, endbuttons and peg finials, we use bone for these items (as is found on most old instruments in these contexts). There is a glossary at the end of this section, which lists the English names of timbers and other materials that we refer to throughout this website; these have been translated into French, German, Italian and Spanish. Timber stocks We have considerable stocks of fine, selected seasoned timbers, most of which have been held for between 10 and 30 years; as well as European woods such as ash, maple, fruitwoods, cypress, spruce, walnut and yew, we have a considerable stock of dry, well-seasoned ebony (including hundreds of sawn leaves of various thicknesses for neck veneers and fingerboards, as well as a large amount of dry, solid lumber which can be sawn for lute, theorbo and guitar ribs) various rosewoods (for non-USA customers) and snakewood for the later instruments. None of these tropical timbers have been obtained in breach of any C.I.T.E.S. or other environmental protection treaties: for example, our stocks of rio rosewood (dalbergia nigra) kingwood (dalbergia caerensis) and pernambuco (caesalpinia echinata) were bought in the early 1970's, and the ebony and satinwood we use was inherited from Stephen's grandfather, a master cabinet-maker Our large stocks of soundboard timber – European Spruce (picea abies) – are supplemented on a regular basis, but since we have ongoing unique access to older stocks of spruce (at any time 10 years +) from the leading supplier of violin-makers' timbers in Bavaria, the player is assured of the best quality of soundboard available anywhere. Much of our spruce stock is of the Haselfichte variety – a type of hard, stiff figured spruce which produces an excellent response across the tonal range (very similar to what is often called 'Bear-claw' figuring by North American timber dealers and instrument makers). Working with rare, expensive or difficult timbers Some particularly rare and/or expensive timbers, such as Hungarian ash, certain maples and poplars, Macassar ebony, certain rosewoods, snakewood and striped heartwood & sapwood yew (as well as heartwood yew) will add a supplement to the basic price. For example, for Hungarian ash, we would charge an extra £600 for a 9 or 11 rib lute back made from sequetially-sawn slices of this very, very rare timber; a striped back is, less at £200 extra. In the context of multi-ribbed back lutes and baroque guitars, striped heartwood & sapwood yew also attracts a price differential, according to the number of ribs; for example, for a 25-rib lute back made from striped yew, we would charge an extra £600. We also charge more for black ebony when used for the back of an instrument – because of the extra work and health hazards involved in working it (£600 pounds for ebony ribs on a Voboam model baroque guitar, for example). We will advise on the extra charge for using rare and difficult timbers at the point of ordering. We are constantly searching-out and discovering interesting, highly-figured, quality timbers; a recent special 'find' was several planks – the entire stock, in fact – of a very rare and unusual European maple (in appearance, it looks like a cross between quilted maple and birds-eye maple, but without the actual 'eyes') which we have already used for several instruments; for images of this maple and a further description, please refer to the section 'Hungarian Ash and Holbein's Maple' further down this page. Another addition to our timber inventory in 2006 was the acquisition of several types of highly-figured Italian and Styrian (southern Austria) poplar, which we have recently used for several lute bodies; we were fortunate to be able to obtain these woods in reasonably large dimensions, thereby creating a wide choice of cuts for sawing into ribs. Earlier in 2007, we obtained further supplies of Hungarain ash – ironically, again sourced in England, as our original supply was, following the 1987 Hurricane, or Great Storm (please refer to the account of this event further down this page). This more recent type presents slightly different grain characteristics to the earlier type we came across, and is similar in some respects to a Japanese ash, or Tamo (fraxinus mandshurica), which sometimes presents a figure similar to 'classic' Hungarian ash, colloquially called 'peanut' figuring in Japan, due to the numerous ovoid figures in the grain. We have used this timber for several customer's orders between 2008 and 2016, and various images of lutes made from this wood can be found throughout the site.

The seven-course lute shown here is made from 'Hungarian' ash (known as Blumenesche in Germany); the eleven ribs of its back were sawn in sequence from the same plank. The player can order with the confident knowledge that our extensive stocks of prime-quality timbers, perfectly seasoned and mature, carefully-chosen and selected by us personally, are available to be selected, sawn, planed, carved and worked to produce a first-class instrument. Black (bog) oak fingerboards and pegs – and lutes! Black (bog) oak – the only native black European timber – was first used by Stephen back in 1975 alongside bone, inspired by the use of the two materials by the Ruckers harpsichord-making dynasty of Antwerp, who used it for their keyboards; this followed a conversation with Stephen's friend the distinguished English harpsichord-maker Derek Adlam, held whilst he was in the midst of conservation work to a Ruckers instrument. At around the same time, Friedemann Hellwig also showed Stephen an original Buechenberg chitarrone lower neck which was veneered with black oak with ivory stripes – suggesting that historically, and at a time and place where ebony was freely available – black oak was considered a rare and precious commodity. We've recently gone a whole stage further and constructed two lutes (an eight-course and a seven-course) whose backs are made from black oak, their fingerboards, pegbox and neck veneers and of course, their pegs, are black oak; images of these instruments appear elsewhere on this site. More will follow in due course. Stephen was the first modern luthier (we'd prefer to use the term 'lutemaker') to use black oak on renaissance lutes in lieu of ebony, but it seems that everybody and their uncle has recently decided to use it. Our current stocks are 5300 years old; this has been dated by Cambridge University, who were provided with samples; the trees from which our timber comes predate the Giza Pyramids, and are more or less contemporary with Stonehenge. How would you like to own a 'New Stone Age' (or Neolithic, if you prefer) lute? From a woodworking perspective, it's an indescribable sensation, running a plane over wood that's over 5000 years old; there's a reluctance to even discard the shavings . . . Across East Anglia, ancient forests of oak, which seemed to have dwarfed modern trees and had a high canopy compared to a modern oak forest, eventually died standing in salt water, and fell into the silt which had once been the forest floor, following the waters of the North Sea having risen to inundate the land of the East Anglian basin around 6000 years ago. Being submerged, the trees were preserved in anaerobic conditions, and were never attacked by woodworm or fungus; many of the trunks which are dug up –typically 2 metres below existing sea levels – are very long and straight, and extremely slowly and evenly grown – comparable in annual ring count and width to the fabled German Spessart oak. The timber, when oiled or polished, has an almost eerie, breath-taking depth of blackness and a sheer presence which ebony simply doesn't possess; and its density – far greater than that of any modern oak species - being very similar to rosewood, means that it is an excellent tonewood which is eminently suitable for lute-making. It's arguably the most exotic European timber (it is found also in the Low Countries and parts of Denmark and northern Germany, where it is known as Mooreiche) and it's not exactly endangered, although, of course, there's a finite amount of it.

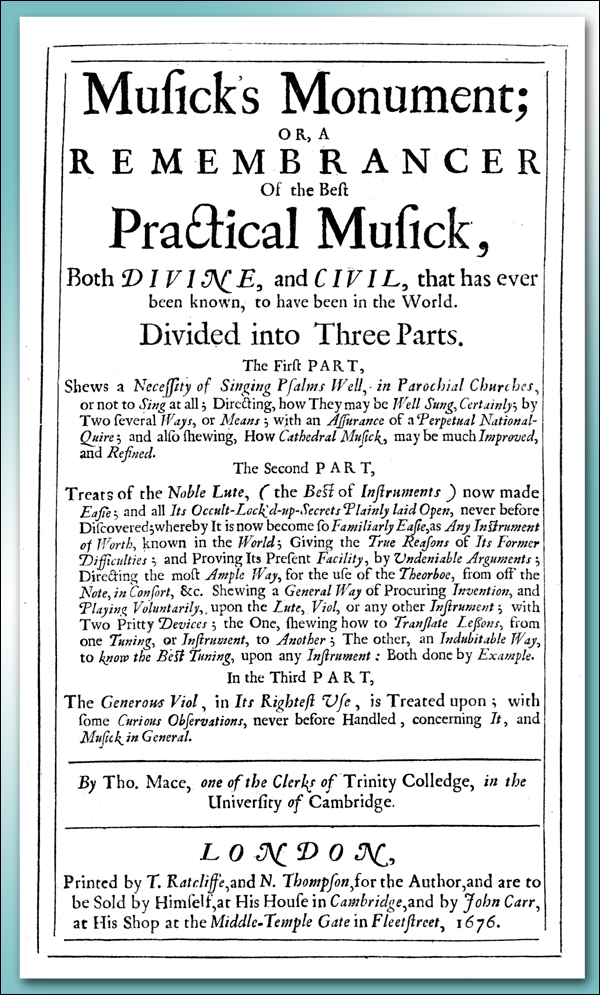

The eight-course lute above was made in November 2016 for David Wilson from Boston, USA, now resident and working in Cambridge – about twenty-five miles from where the tree-trunk that yielded the timber we used for its ribs, fingerboard, neck and pegbox veneers, tuning pegs, and half-edgings came from. Dalbergia (rosewood) species ban (USA only). On 2nd January 2017, the United States government, acting in conjunction with CITES, introduced legislation which severely restricted the import into the US of newly-manufactured items made from or having any component parts made from any and all Dalbergia species timbers. Older or pre-existing items made from or containing rosewoods faced similar restrictions, and the legislation is likely to become tougher in the near future, with a wider scope; for example, an export permit is currently required to transport a classical guitar made from Brazilian rosewood across an international border. The intended targets are dalbergia nigra / Brazilian Rosewood and dalbergia latifolia /Indian Rosewood, although other Dalbergia timbers which are in common use such as Kingwood (d.caerensis), African Blackwood (d. melanoxylon) and Tulipwood (d. frutescens) are included; but all lesser-known rosewoods of the dalbergia genus are included. However, there is a solution: back in 2015, knowing the ban was imminent, for US customers we began using Santos Rosewood (machaerium scleroxylon) also known as Bolivian Rosewood, which is currently not on a CITES endangered or banned list; its tonal and physical qualities (density and elasticity and so on) are – in our experience – the equal of 'real' rosewoods, and visually – because there is such a variety of colour and pattern available in this timber – it's relatively easy to match its grain with the rosewoods. In all descriptions of available models throughout the Catalogue pages of this website, 'rosewood' should be taken to mean Santos Rosewood, machaerium scleroxylon. Instruments affected include certain theorbos, archlutes, baroque guitars and baroque lutes; at the moment, ebony, snakewood and pernambuco (used for tuning pegs) are okay. Tuning pegs made from pernambuco / Brazilwood (caesalpinia echinata / paubrasilia echinata). We have, since the late 1970's, used pernambuco (known also by its original name of Brazilwood) for tuning pegs on some lutes, vihuelas and guitars. Pernambuco lumber is banned, but turned tuning pegs are exempt – they perforce comply with the legislation definition of 'manufactured'. This exemption embraces pegs, because they are machined and shaped, and thus fall within the definition of 'manufactured'. Old pre-CITES material – which is what our stocks are, having been sold to us as old stock by W.E. Hill & Sons (Bond Street, London violin dealers and bow-makers; then Centuries-established, but now sadly defunct) in 1975 – is OK. Lacey Act (USA only) For US customers, we guarantee that we ensure that all timbers we use in making your instrument are Lacey-Act compliant, and we are experienced in providing the required documentation for the requirements of the current Lacey Act legislation. Timber preparation All stages of making our instruments are carried out in-house, using hand tools; we do not use production machines of any sort, or outsource the making of any elements such as guitar rosettes. We saw all of the wood used ourselves, from the plank or log – this includes all of our lute and vihuela ribs, guitar backs and sides and ebony veneers (except for soundboard wood, which we buy ready-sawn, not 'in the log'). The old lutemakers had their supply-lines available to hand, with timber dealers, specialist sawyers, veneer-cutters and other trades existing to supply the demand for materials from instrument makers; there are even accounts of lute-ribs being prepared during the long, cold and dark winter months by mountain village communities as a winter activity, when other farming and rural work was perforce impossible. So we probably do far more sawing than any of the old makers personally did. For those interested, we saw everything using two single-phase 30 year-old Startrite 352 bandsaws, fitted with 3 Tpi skip-tooth blades, 20mm wide, 14 thousandths of an inch thick (sorry, but that's how their Swedish makers describe them, by a mixture of metric and imperial measurements) and these blades remove a kerf of only 0.6mm or so. They're so accurate that it's possible to saw eight 1.4mm thick slices from a piece of material 16mm thick (allowing for cleaning-up the sawn surfaces) and they'll accurately deep-saw maple, rosewood or ebony at 200mm. We also prefer to convert and saw all of our own timber, because one of the many enjoyable and rewarding aspects of making early plucked stringed instruments is the sheer variety of woods that you get to work with; plus converting timber from its raw state into, say, ribs for the back of a lute is a lot of fun, and for us a vital part of the process of instrument making. Holly Many old lutes and guitars were constructed from and decorated with ivory; it was also used as a narrow white spacer between darker ribs on a multi-ribbed back. We use Holly (ilex aquifolium) which is an excellent visual and structural substitute, being almost pure white and without strong grain lines or features (our wood is felled and converted only during a bitterly-cold winter, when the sap is low and does not cause discoloration, thereby maintaining the ghostly-white hue of the holly). We also use bone where appropriate, and have experimented with a form of celluloid, a white organic plastic, as an ivory substitute in certain contexts where holly would not be appropriate. However, as far as possible, we avoid the use of anachronistic materials. Interestingly, a product design student from the famous London Central St Martins art school, Sinnøve Fredericks, contacted us in early 2006, asking about holly wood – having 'Googled' the word 'holly' and turned up the reference above. We were able to advise her on working the wood, we supplied her with material for her project, and lent her some tools (piercing-saw, small clamps and so on) to help her move her project forwards; the completed piece formed part of her degree show in June. This was quite an interesting 'completion of the circle' for Stephen, since his background was art school, having done a foundation course at Hornsey College Of Art back in 1971. One of the visiting tutors was Keith Critchelow, a disciple of Buckminster Fuller. It was nice to give something back to the world of design, and especially rewarding to be able to help one of the current generation of art students – who are tomorrow's design leaders and innovators. Glues Only the best quality hide-glue and isinglass (fish-glue) are used for building our instruments; we don't use modern PVA-based or other resin adhesives, which suffer from 'cold-creep' and are completely unsuitable for assembling musical instruments, in our opinion, or others such as Titebond. PVA-based and aliphatic resin glues and other modern 'woodworking' adhesives never completely set hard, consequently their use means that a 'shock-absorber' is being effectively placed throughout the instrument, which of course can only deaden and compromise the sound – no 'ifs' and no 'buts'. None of these modern glues ever sets hard (except for cyano-acrylates and epoxies, but – although we know of at least two modern makers who stick their bridges on with two-pack epoxy resin – this to us is so daft and short-sighted, that it should not even be on a list of options anyway). Only hide glues, bone glues and fish-glue (isinglass) provide an intimate wood-to-wood joint, set glass-hard and can be reversed for repair purposes without damaging the surrounding wood (and with organic glues, there isn't a ghastly mess to laboriously clean-up, as there inevitably is after use of modern resin glues – animal glues can be cleaned-up as you go using hot water). Anyway, if you owned a Stradivari violin, you wouldn't expect a violin repairer to work on it using modern glues, so why use some daft modern product – the long-term effects and longevity of which are perforce unknown quantities (and none of them is easily reversible for repair purposes) – to make new instruments, when we know that there are artifacts over 4000 years old which were assembled using animal glues, which are still stuck together? If it was good enough for the old lutemakers, it's good enough for us; gelatine and fish glues are what we can confidently be sure the old masters used for their instruments, and it's hardly rocket science: all you need is a glass jar with a lid (absolutely not an iron pot or – notwithstanding what Mace says below, a lead container – for health reasons) a saucepan, a hotplate with a temperature control and a brush (and you definitely don't need a silly electric glue-warmer, just the aforementioned items and some common sense). An iron or steel container for the glue will simply darken it, producing unsightly and unwanted dark glue lines, as well as discolouring the surrounding water in the saucepan. Isinglass / Izinglass Isinglass has been used for centuries: Thomas Mace, writing in Musick's Monument in 1676, tells us, on page 55, in reference to lute repair and maintenance:

"Have ever in readiness some of the Clearest and Best made Glew, together with Izing-glass, (both which mixt together make the Best Glew)". 'The time has come', the Walrus said, 'To talk of many things: Of Fokkers and fishglue – of cabbages – and kings . . . Well, Fokkers and fishglue, anyway (with apologies and very sincere homage to the great Lewis Carroll – one of our heroes): Stephen's grandfather was a cabinet-maker, and he used isinglass (mixed with gin – as we still do today) to glue brass and other metal inlays into wood; we possess an ashtray that he made from the wreckage of a German plane he shot down in 1917 (he was a fighter pilot during the first World War). He used a section of its laminated mahogany propellor, mounted with copper from its fuel tank in the ashtray's design, and stuck metal to wood with isinglass-based glue. So using isinglass (and of course enjoying a gin & tonic 'sundowner') is a family tradition; and there can't be many workshops where gin is a tax-deductable item: Bombay Sapphire for pleasure, Gordon's for business . . . Hogarth is probably turning in his grave. But neither of us smokes, so the ashtray is a treasured momento and heirloom, rather than a practical object. And to extrapolate further upon the Carroll quote: the sea isn't usually boiling hot, and pigs don't have wings; and as far as we're concerned, gelatine-based glues and isinglass are the only real choice for assembling musical instruments, not some yellow gunge sold in 40-gallon drums.

The seven-course lute shown above (with a shaded yew back) was originally made in 1980, just after Stephen moved to our workshop in Peacock Yard; it came back early in 2004 for a new soundboard and bridge, following some accidental impact damage. Over the quarter of a century since it was made, not a single glue-joint had opened or failed – a testament to the use of animal glues used throughout. All joints and surfaces – including the bridge and ebony veneer of the neck – were then, as now, glued with animal glue combined with isinglass. It was a nice opportunity to 'refresh' this lute, which had given its owner – Michael Bruhn, of Kiel, Germany – much playing enjoyment. In November 2012, we made Michael a 10c lute, he having been so imperessed by the rebuild and the improved sound of the 8c above. Varnishes We finish instruments which are made from white woods (such as maple and ash) yew and fruitwoods with a transparent, coloured oil-based amber varnish, using a formula similar to that used by the old violin makers. Of course, since the art of lutemaking pre-dated that of violin-making, the original 'violin' varnishes were actually adopted from existing varnishes used by lutemakers. We try and match the colours that we use to those found on original lutes, bearing in mind that the majority of original lute varnishes were nowhere near as dark as many surviving museum examples now present. And for example, when contemporary paintings are cleaned, and the original colours can be viewed for perhaps the first time in centuries, many of the wood-tones are seen to be much paler and brighter than before, when the original paint surface was often obscured and masked by centuries of over-varnishing and indifferent curatorship. A very good example of a cleaned painting revealing a surprising wealth of hitherto veiled detail and colour is The Ambassadors, by Hans Holbein, 1533 (a detail from which – showing the famous lute – can be seen further down this page). A lot of surviving instruments were also over-vanished or even refinished in the 18th and 19th Centuries, when the concept of retaining an original varnish on a lute back was not something that was observed by many of the workshops and dealers through whose hands old lutes passed. We make our own-recipe oil-based amber varnishes, very similar in formulation to old varnish recipes. Since the formulation, making and application of varnish has always been considered by some to be a bit of a black or alchemical art, we thought that the following illustration and text might shed some light on a process which is often shrouded in mystery and secrecy . . . Somewhere, in a secret location on the plains of the river Po near Cremona:

Two violin makers and a lutemaker grapple with the grinding of the mystery ingredients of the fabulous, near-mythical 'lost' Cremona varnish (the figure on the far left is thought to be Niccolò Amati, the lutemaker on the right one of the Tieffenbruckers; note that they are all wearing traditional varnish-making pantaloons). The lucky violin makers are thought to be using a perpetual-motion device, whilst the poor old lutemaker is having to make do with something he has apparently lashed-up from the flywheel of an early (wooden) small-block Chevy V8*. The essential ingredient of the 'lost' Stradivari varnish recipe was, of course, pure Phlogiston, which was gathered in a secret location in the Piedmont foothills – always under a full moon – by Antonio's son, Omobono. We use organic Phlogiston in our own varnish, ground using an apparatus similar to the one on the right in the image above. Nothing changes . . . varnish-making in the 21st Century hasn't really progressed much further, and this kind of performance can still be seen taking place here in Peacock Yard from time to time . . . naturally, when the moon is in its most propitious phase, and the cosmos is in alignment. The resultant varnish is left to simmer whilst breathed upon by wild, unpredictable winds, and it is subjected to a torrent of obscene gestures and profane aphorisms . . . just like in the old days, in fact. Then we apply it with a brush made from hairs from the tail of a Unicorn, whilst the gently beating wings of Pegasus help it to dry . . . *We sourced one from a Cosworth YB, from an RS500. Lute roses, guitar and vihuela rosettes. We knife-cut all of our lute roses, and make special metal punches to make the guitar and vihuela rosettes – we do not buy these in from other workshops, they are all made by us.

On the left, a copy of a Lute rose, from the Hans Frei lute (c. 1540) in Warwick Castle; next to it is a copy of a rosette from a guitar by René Voboam, 1641 (made from parchment, in 5 tiers - the soundhole edged with ebony & bone stripes). Both made by Sandi. Interestingly, many of the old makers were involved in the making and supplying of rosettes and other parts of instruments, as this reference to the activities of Giorgio Sellas (from a document dated February 19th, 1637) makes clear: "In the presence of this notary and undersigned witnesses, all business owners in this City that I recognise, it is stated under oath that the ship San Giacomo docked in the port of Malamocco, Venice, bound for Spain, was loaded with the following goods to be delivered to Mr Alessandro and Francesco Mora in Lisbano; to the above mentioned Mr Mora: one box of guitar tables of good quality purchased from Mr Giorgio Sellas, violin maker of this city, who has them delivered from Germany . . ." Stringing We are able to supply instruments fitted with either gut strings from Aquila, Gamut, Kathedrale, Kürschner, or any of the various modern string materials used, including nylon, carbon, nylgut or overspun strings of the type made by Aquila, Kürschner Pyramid, or Savarez. Stringing recommendations & string tensions We fit our instruments with strings calculated to work at a certain pitch; you should not attempt, for example, to tune a lute which has been fitted with strings at 415 Hz, up to 440 Hz unless you change the strings according to our recommendations, otherwise you will be subjecting the instrument to possibly damaging extra tension. With over fifty years of combined experience of building early plucked stringed instruments, we know what works and what doesn't: we fit our instruments with string sets that will allow them to work at their best, and having always worked closely with leading players, string makers and developers, we are happy to pass on to you the benefit of this experience in order to help you with any stringing problems or issues you may have. All of our instruments are supplied with a comprehensive printed string chart, which also includes the diameters of gut frets fitted. We can also advise on alternative stringings (for example, if you have bought or ordered an instrument fitted with modern strings and wish to string it in gut – or vice-versa – we are more than pleased to advise). Gut strings

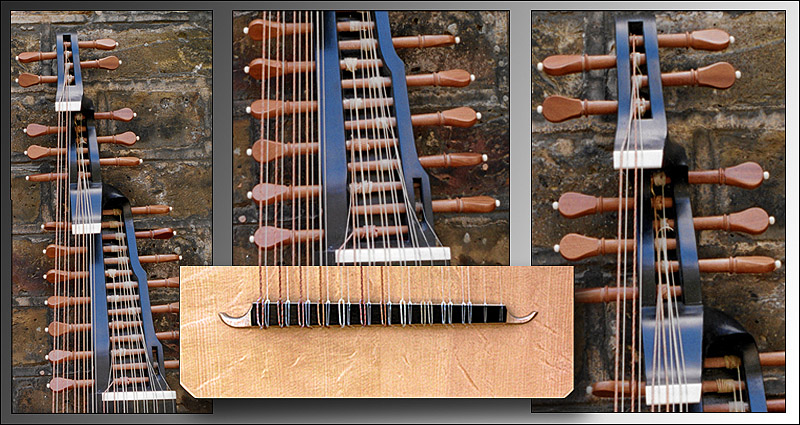

Above: details of the bridge and pegbox of a thirteen-course triple-pegbox baroque lute fitted with Dan Larson's 'Gamut' gut strings. Please note: Because of the relatively high expense of gut strings, we add their cost to the total for the finished instrument. Nicholas Baldock / Kathedrale We have been using for some time the 'Kathredale' gut strings made by Nicholas Baldock in Germany; Nick formerly worked for NRI and Kürschner, and a few years ago set up on his own and started producing his own gut strings, which have been very favourably received by all who have tried them. The gut used is softer than many offer, and the thinner strings seem to last longer, whilst the basses, particularly on 6 & 7 course lutes, baroque guitars and vihuelas, have a very convincing full and rounded sound. Nick does not have a distributor, he sells direct. Nick works in Diez, Germany. He can be contacted on +49-(0)6432-920849 telephone, (-920946 fax) or +49-(0)173-9200571 mobile/cellphone. Nick's email address is: Kürschner Strings We use and recommend Bernd Kürschner's 'Luxline' strings as diapasons for archlutes and theorbos, they are particularly successful, in our opinion, and more convincing than 'loaded' strings, which seem to have a tendency to be inconsistent. We have known and worked with Bernd since 1984 (we struck up a lasting friendship over several weißbiers at the Herne exhibition of that year) and his strings are superb. Bernd works in Mainz, Germany. kuerschner@kuerschner-saiten.de Dan Larson / Gamut We first fitted Dan Larson's Gamut-brand strings to a 13-course swan-necked baroque lute and an archlute (in September 2005 and January 2006 respectively), and were very impressed by their sound and stability, and have used them many times since; Dan is an old college friend of Stephen's (we go back 30+ years). Dan works in Duluth, Minnesota. Dan can be contacted on +1-218-724-8011 (Toll-Free phone/fax within the USA: 1-888-724-8099) or email: website: Metal strings Wire-strung instruments are supplied with specially-made metal strings, their compound (twisted or overspun) strings are made to our own specification. Please let us know your stringing preferences at the point of ordering. Fretting Gut frets are always fitted, except where the original instrument had fixed metal frets, for example members of the cittern family, orpharions, bandoras and the chitarra battente. We do not fit nylon or any other type of plastic tied frets. We strongly advise against the use of plastic frets (made from fishing-line or old strings), since – as most modern players now know – they are a nuisance to tie satisfactorily, they are not easily available in the grades necessary for lute, vihuela or guitar frets, and they give an unpleasant sound. We fit single or double frets as standard; single frets are easier to tie and of course use less gut than double frets do, and it has to be said that the majority of modern players prefer single frets. However, double frets last longer, as they have the advantage that the loop nearest the bridge is the point at which the string vibrates to create the sound, whilst the loop nearest the nut 'takes the strain' of the vertical pressure applied to the string when it is fretted; this means that the 'front' loop (ie the one nearest the bridge) can last longer than a single fret would. The 'rear' loop sometimes takes a while to 'bed-in' and a little buzzing can be encountered whilst it does so, but this soon disappears; the principal advantage of having double frets fitted is to combine longevity with their more secure grip upon the neck and fingerboard. The 6-course lute depicted so clearly and accurately in Holbien's paiting The Ambassadors is fitted with double frets. The use of gut stringing throughout would perforce mean that gut frets last much longer than would be the case with modern synthetic and overspun strings. We are pleased to advise on fitting frets, and we'll gladly demonstrate to visitors to the workshop the technique of tying gut frets. In this regard, we often find ourselves being asked by players performing in the concerts at the various exhibitions and festivals we attend, to replace their instrument's frets; it's interesting to note just how many professional players hate doing this simple task. We recommend that players use a small pair of pliers (pincetures) to grip the 'short' end of their preferred fret-knot, as this means that one's fingers are not stressed prior to playing the instrument; a small, low-wattage soldering iron (preferably fited with a hook or clip to safely hang it by) is the safest and neatest method of burning-down the ends of the fret-knot once tied and pulled tight, just prior to pulling it into place along the neck. We recently saw yet another lute whose neck and pegbox had been scorched because the player had used matches or a lighter to burn his fret-knot ends down . . . the late, great Tom Finucane once attempted a tongue-in-cheek defence of using a lighter, as he felt it echoed for the lutenist the blues guitarist's habit of jamming a smouldering cigarette on one of the string ends whilst playing. Measuring your fret and string diameters accurately We'd advise all players to equip themselves with a digital caliper, so that fret and string diameters can be accurately measured and checked; a typical example – listed at $50.98 + shipping – is available online from Stewart MadcDonald, the Athens, Ohio-based luthiers' supply merchants (the current Stewart MacDonald code is #5212). It is illustrated in their current International Catalogue and on their website: Players living in Germany can source such a device more cheaply from Tschibo, who have outlets in various supermarkets such as Aldi, and more recently, Tschibo products have become available in the UK at selected branches of the supermarket chain Somerfield (Tschibo offers a range of useful domestic and practical products). The price in the UK is around £10-99, in Germany €11. Provided that these devices are handled with care and their batteries are changed when necessary, they should provide several years of useful service. Temperament If you have preferences regarding temperament, we are happy to discuss this and work closely with you; as well as equal temperament – still favoured by many players – various forms of meantone fretting can of course be used. We will need to know which one you prefer before the instrument is collected or shipped, so that any fixed wooden body frets can be set properly. Fretting and temperaments greatly exercised the old players and theoreticians, and the subject rightly has the capacity to be a highly-charged personal and subjective matter today; we respect the sincere passions and opinions aroused by this issue, – after all, we are passionate about our instrument making – and try to respond accordingly, working with the individual player to achieve a mutually satisfactory and workable instrument. Where wooden body frets are concerned, if you are uncertain about your preferred temperament or are experimenting, we would advise that these are only lightly glued in place, to enable their being moved without marking the soft spruce of the soundboard; we are happy to give precise technical advice regarding the glueing of fixed body frets. Cases Cases are not included in the prices quoted for the instruments. We recommend and supply Kingham MTM Cases, which are individually made by expert craftsmen and are in our opinion simply the best available.

A typical Kingham MTM case is shown here, this example for a six-course lute. If a case is required it must be ordered at the same time as the instrument, and Kingham MTM will invoice the customer separately for the case; they can be paid directly via Credit Card, and accept Visa and Mastercard, but not American Express. Please specify if you want a carrying strap when ordering the case. Cases are made with black outer coverings and crushed velvet linings in a choice of colours in standard form, and are lockable; plain velvet lining is available, as is glass-fibre reinforcement for extra protection, at extra cost (although this option makes the case slightly heavier than the standard model). Other colours of case covering are available to special order, including dark green, dark blue and white; for the full range and specification of their products, please visit Kinghams' website: Carrying straps can be supplied at a modest cost. Our guarantee Our instruments are guaranteed against any faults or defects in workmanship or materials for a period of 24 months from the date of completion, providing reasonable care has been taken over handling and maintaining the instrument, and its stringing, pitch, tuning and storage conditions have been followed according to our recommendations (for example, a chitarrone designed and strung to be played at 415 should not be cranked-up to 440 or even 466 – this sort of action would of course void the guarantee, since it would subject the instrument to a dangerous amount of extra tension). Should you want to change the pitch of the instrument to a higher one (and not endanger the instrument, and continue to enjoy the protection of the guarantee) then you must change the strings to thinner gauges to maintain the balance of the overall tension, and according to our recommendations; we can advise on appropriate re-stringing in these circumstances. We are sufficiently confident in our experience, workmanship, glue and materials to offer a relatively long guarantee, the caveat being that we expect the player to treat the instrument with care and respect; of the thousand or so instruments made by us over the last 30+ years, only three have ever had their bridges come off, for example – and all three of these incidents were due to careless treatment and storage of the instrument. Relative humidity We recommend the use of a humidifier if you live in a country where there are very cold (and hence very dry) winters, dry summers or other seasonal weather extremes, or if your apartment or house is fitted with modern central heating. Lutes, early guitars and vihuelas were not designed and developed to exist in such conditions, so it is vital that you equip your music room (at least) with a humidifier and a hygrometer to monitor the ambient temperature and humidity. Several types and models of 'weather station' are easily available; we recommend an excellent digital hygrometer made by Oregon Scientific Instruments (Model No. EM-913R). An alternative is available from Stewart MacDonald, the Athens, Ohio-based luthiers' supply merchants (the current Stewart MacDonald code is #5337): Should repair work become necessary following accidental damage, we prefer to carry out any such work ourselves, to prevent your instrument falling into inexperienced hands. We use only the choicest materials and glues, and call on a combined experience exceeding 60 years of researching and building lutes, theorbos, early guitars, wire-strung instruments and vihuelas.

The October 1987 Great Storm Many of the timbers we use – apple, ash, cherry, holly, lime, maple, pear, plum, poplar, walnut and yew – were collected in London and its environs, following the devastating October 1987 hurricane, often referred to as the Great Storm. These included beautifully-figured rippled ash, Hungarian ash and various maple species – one tree which fell on Clapham Common, south London, yielded over 30 cubic feet of figured maple*. We also have large stocks of Osage orange (maclura pomifera) Pagoda tree (sophora japonica) and Californian Laurel (umbellularia californica) given to us by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, London, which have proved to have excellent accoustical and structural qualities; we have so far used them for making earlier renaissance lutes, mostly six-course instruments.

The wish often made in jest by those interested in exotic timbers – to go around Kew Gardens with a chainsaw – became tragic reality following the hurricane which swept across south-eastern England during the night of October 16th-17th 1987. Thus on a cold bright winter morning in early 1988 we found ourselves invited to do just that (above); the timber being sawn here is a mature Osage Orange (native to the area west of the Mississippi river) which sadly was a victim of the winds that night. This tree was around 130 years old, and is referred to by Alexander Howard, writing in Timbers Of The World, first published in 1920, on page 434, where he states: "Fine trees have been grown in various parts of this country, and especially at Lord Aldenham's seat near Radlett in Hertfordshire, and also at Kew". We also acquired considerable stocks – from Kew and other tree collections – of Persimmon (diospyros keaki and diospyros virginiana) – which has dense and black heartwood, and is the equal of any African, Ceylonese or Indian ebony, and is emminently suitable for fingerboards, ribs and neck veneers. We principally reserve these timbers for US customers, because Persimmon is an ebony-family tree which yields black timber which also happens to be Lacey Act-compliant, being a non-endangered, temperate-zone hardwood. Grown in London and harvested by us in the wake of the 1987 hurricane. In 1990, we built a 6-course lute, its neck, pegbox and fingerboard made from Pagoda tree, and its ribs from Osage orange striped with Pagoda Tree, for the permanent collection of The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; as part of 'The Thread Of Life', an exhibition housed in the Joseph Banks building, Kew, which explored the reliance of humankind upon cellulose. This instrument is now on display in the Kew Gardens Wood Museum. Walking around the area where the photo above was taken still sends a shiver up the spine, when one recalls the magnificent tree which once stood there. We are currently working on a 6-course lute, the back, neck, pegbox, pegs and fingerboard of which will be from this Osage orange tree from Kew; images will appear here shortly. More details are in the section on Raymond Fugger, further down this page.

Milling another of the Kew logs - Pagoda tree – in Peacock Yard in early 1988 – using a Sperber chainmill fitted with two Stihl 094 motors (and yes, Stephen does still have both of his legs – you can always rely on a good pair of Doc Martens). The hammer was used to drive the orange-coloured plastic wedge (next to it) into the sawcut, to support the cut plank immediately before running the saw out of the timber, to thereby prevent it dropping onto the chainbar and trapping it. For at least two years after this devastating event, a Stihl chainsaw was as essential an item in the car as an A-Z map; and the chainmill – a wonderfully-useful example of 'small-planet' technology – allowed us to break-down and transport huge, otherwise impossible-to-move logs in the aftermath of the October 1987 hurricane. Amidst the hard work, there were some hilarious moments: a park warden at Clapham Common, when we asked him if we could have a large, highly-figured maple which had fallen, replied mockingly "If you can move it, son, you can have it". The expression on his face when we produced the chainmill, went crash-bang-wallop and did just that in 1 hour flat (see below) was priceless . . . *Below: 'crash-bang-wallop' on Clapham Common . . . not bad for one hour's work – 30 cubic feet of prime, figured maple for free – and that hour included bagging-up and removing from on-site the chippings produced by the chainsaw.

Top left, to right: man finds tree – man removes business end of tree – does my butt look big in this? And the chainmill came with a rose-cutting attachment, as you can see in the background . . . A large number of lutes have been made from this wood, and we also gave a large piece of it to a Dutch colleague, violin-maker Bart Visser, who used it to make a one-piece back for a beautiful copy of a Rombouts cello. Bart knew a good piece of maple when he saw it, but many other violin makers who like to kid themselves that the hardest maple only comes from mountainous areas (they usually fall for the trade baloney that it all comes from the Alps, whereas in reality most of the stuff they buy comes from Scotland – and is re-sold to them as 'mountain' or 'Alpine' maple by German and Swiss dealers – go figure) ought to consider this: when we were sawing the tree above, we burnt-out one of the Stihl 094's (094's were at that time the most powerful motors that Stihl produced) because this Clapham Common wood was so bloody hard – harder than any oak we'd been milling at the time. Hard, crisp, white, figured, and 'on the doorstep' – and moreover free: it doesn't get any better. A metal-detector for the random nails and chunks of downed Messerschmidt and Stuka (and other Fokker's) engines occasionally found in London trees was also vital (we learnt this the hard way after taking all of the teeth off of a milling chain when we hit what were clearly aero-engine bearings in a Tree Of Heaven in Kennington Park, south London – the resultant fireworks-display of sparks in the descending twilight was spectacular, if somewhat depressing). And Ford probably never knew just how useful the 4x4 estate version of their Sierra became to us, or just how large a log could be shoved inside one.

The left-hand image above shows the Sperber chainmill in action on Clapham Common, south London, planking a fallen lime tree; this and a second lime from Kew Gardens continue to provide the limewood we use for neck blocks and neck cores (where a neck is veneered). The central photo was taken in February 1988, in a park in north-west Kent, less than an hour's drive from our workshop, and shows the ash tree – blown over in the October 1987 Great Storm – that yielded our present stocks of Hungarian ash (see images of the lute, below); the first two planks cut are already loaded onto the trailer; it and the Land Rover were fitted with special 'balloon' tyres so that we could drive across parkland to get to fallen trees without churning-up or damaging the grass. On the right can be seen the Trekkasaw portable bandmill, which was also used to cut more accurately-sawn planks; a walnut tree is being sawn here by Stephen's friend of more than thirty years, Robin Carter, outside our workshop in Peacock Yard. Robin, through his company Timber Resources International, supplies a range of specialist timbers, as well as offering mobile sawmilling: The chainmill is a useful way of quickly planking and removing a log from onsite, in thicker sections, whereas the Trekkasaw is more suitable for accurate, finer sawing with less waste, particularly in Robin's expert hands. Hungarian Ash and Holbein's Maple

The instrument shown above – a six-course lute tuned in a' – was made largely using timbers from the 1987 Great Storm; its neck and pegbox are of walnut from a tree which blew down in south London, its bridge from holly from Hyde Park, and its neckblock of lime from Kew Gardens (the soundboard is of course from spruce sourced from Bavaria). The back is from two cuts of Hungarian ash (from the tree shown being sawn in the centre of the three images above this one); this variety of ash – known as Blumenesche in German – was used in three of the five surviving lutes by the great Augsburg-born lutemaker Laux Maler, who would have grown up knowing just how highly-prized this timber was in his time (just as it is now). Hungarian ash Hungarian ash is a variety of European ash (fraxinus excelsior) the earliest supplies of which historically came from Hungary – hence its name. In this case, our stocks came from Kent, the Garden Of England, but it's identical in appearance to all of the Hungarian ash we've seen used in old instruments, furniture and panelling, and it's certainly much harder than other types of ash. We still clearly remember the thrill of realising that the apparently plain ash log had in fact around one-quarter of its area comprising this wild, beautiful grain; like the 'Holbein' maple described further on, we'd all but given up hope of ever finding Hungarian ash – we certainly didn't expect to find it in Kent! Having made a large number of lutes using this strikingly-figured wood, we've observed that its hardness and density help to produce a crisp and clear sound; ash is without doubt an excellent material to make a lute back from – it was used by Laux Maler for the backs of two of his surviving instruments – and this highly-figured and beautiful variety subtly adds an extra aesthetic dimension to an already brilliant material's acoustic qualities (that is, if you happen to like its unique appearance! ). Hungarian ash was obviously always a highly-prized and precious wood: there is a whole room in the old Rathaus, Regensburg, dating from the fifteenth Century, which is panelled with it, and it is known that it took the original craftsmen twenty years to find enough wood to use for the panels which cover the walls and ceiling (the room is around ten metres wide and fifteen metres long, with a ceiling height of five metres). There is also an altar in the Wartburg, Eisenach, which has Hungarian ash panels, which are clearly worked into the design as a special feature. One of the earliest known harpsichords, made in Leipzig in 1537 by Hans Müller, has its bentside, cheek, tail and spine from Hungarian ash (this instrument is in the collection of the Museo degli Strumenti Musicali, Rome). Our friend and colleague Christopher Clarke, the distinguished fortepiano maker who lives and works in Cluny, once remarked that when he was working in the restoration lab at the Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nürnberg, in the early 1970's, he'd been surprised to discover that some Bavarian train carriages had panels and mouldings from this rare and beautiful wood (they're not around today – we wonder what happened to the wood when the trains were taken out of commission?). It's therefore very satisfying (and rather humbling) to look back and know that more than twenty years on from the aftermath of the Great Storm, the hard work of gathering and sawing fallen trees – the majority of which would otherwise have been burnt rather than used in any way – has resulted in many of the instruments we build today – all of which have some timber from the Great Storm in them, many including the 'Hungarian' ash we found in Kent. We discovered some more of this exquisite timber in March 2007, hiding away in a woodyard in the north of England; this variety looks a little 'quilted', and we've subsequently built quite a few lutes using it, having bought the whole tree. Like the original supply which came to us after the 1987 Great Storm, this wood is a beautiful creamy colour, and has a gorgeous, nutty scent when sawn and planed. The eminent timber authority Alexander Howard, writing in Timbers Of The World, in 1920, recorded that much of the old wood called Hungarian Ash originally came from Transylvania . . .

. . . and whilst 'kind of' on the subject of Transylvania: The composite image above shows two views of the same instrument; the nine-rib back of this seven-course lute is made from four slices of Hungarian ash, sawn in sequence and bookmatched, striped with five ribs of a different cut of Hungarian ash from a different tree. We think that the different way in which the light penetrates the two timbers – something which would not ordinarily be observed – and in this case only made possible because the soundboard had not been fitted when the photo on the left was taken – makes for a very interesting and unusual, and slightly other-worldly image of a lute. The image on the left was produced by shining a light into the bowl of the lute without the soundboard in place, and the beautiful translucency of the Hungarian ash ribs can be clearly observed. It's interesting to compare the two images: the one on the right was taken after the lute had been assembled and finished, with the varnishing of its back being completed. Comparing the appearance of the grain of the raw wood when lit from within by a strong light, with its finished, varnished surface (the one which would normally be seen) is, we think, a fascinating exercise. There is another image of this instrument, backlit again, on the Gallery page. 'Holbein' maple Unusually-figured ash is not the only timber we've been using in recent years with strong historical antecedents; in 2004, we made the backs of three instruments – a 6-course similar to the lute shown above, and two 10-course lutes – from a very rare and unusually-figured European maple species, which closely resembles the timber of the lute in the famous Hans Holbein 1533 painting The Ambassadors (London, National Gallery – see below). Having now obtained a supply of this timber, we will be making further instruments using it, including a 'copy' of the Ambassadors lute – now that we are confident that we have finally located the timber so accurately painted by Holbein. The timber Holbein painted must have been of European origin, and not a North American maple, because birds-eye maple – which only grows in the north-eastern United States and Canada – simply was not known in Europe in 1533; and quilted maple – which only grows in the Pacific north-west – is even more unlikely.

Having wondered for many years if we'd ever find anything like this maple, we stumbled across it whilst searching for something else (in Romania); it looks like a cross between a quilted maple, birds-eye and a burr, with a gentle but definite 'three-dimensional' character. Anybody familiar with the painting will know the effect, clearly seen in the image above. The three close-up details shown in the lower half of the image above are from a 10-course lute we made in late 2004 from this beautiful timber. We've made the backs of several lutes (close-up details of one of them are shown below) from a very rare and unusually-figured European maple species, which closely resembles the timber of the lute in Hans Holbein's painting The Ambassadors. This timber is used as four of the back ribs of the famous cittern by Girolamo Virchi (the one with the carving said to represent Lucretia Borgia stabbing herself through the heart) which is in the collection of the Kunsthistorischesmuseum, Vienna. 'Quilted' and 'flamed' poplar It's rare to find figured poplar, since this timber is usually found with straight, unremarkable grain characteristics; however, we were lucky to have recently obtained stocks of two very highly-figured varieties of poplar, from southern Austria and the Italian Alps. The Austrian poplar has a wild, quilted figure which looks absolutely stunning on a lute back; we first used it for the back of an 8-course lute in mid-July 2006, which turned out very well, and looked stunning (see below); we've placed these detail images of it here, to give an idea of what it looks like. We built a second 8-course lute in August that year, using wood from the same plank, which was bought by a player in Wisconsin, Mark Meier (for further details and images, please refer to the 'Instruments available for sale now' page). We have limited stocks of this rare and beautiful timber for only a few more instruments.

Close-ups showing the typical grain of the Austrian poplar: it visually recalls quilted maple, and is equally wild in appearance, although a lot harder than quilted maple can often be. The images shown above are from an 8-course lute made in July 2006 for Bruce Butler, a classical guitarist living in Buckinghamshire, England. The next instrument (also an 8-course lute) we made using this timber went to Mark Maier, of Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, USA, in October 2006. We've

used the Italian poplar – which has a beautiful and interesting

flamed figure which stands in almost diagonal rectangles – on two

lutes, both 10-course instruments (one of which is shown below). One

was bought in late December 2006 by Chris Hurley, of Sutton Coldfield,

England; images of this instrument are shown below, and can also be

seen on the Instruments available for sale now' page; the second was

bought by Peter Matthews, of Higham Ferrers, England, in May 2007.

Instruments available for sale now

These figured poplars – both being mountain-grown – are very hard, work very well acoustically, and are emminently suitable for lute backs; along with the Hungarian ash and Holbein maple, they make exciting additions to our repertoire of interesting and beautifully-figured European timbers. Translations of timbers and other materials used

Thomas Mace's account of woods used for lutemaking in Musick's Monument (1676)

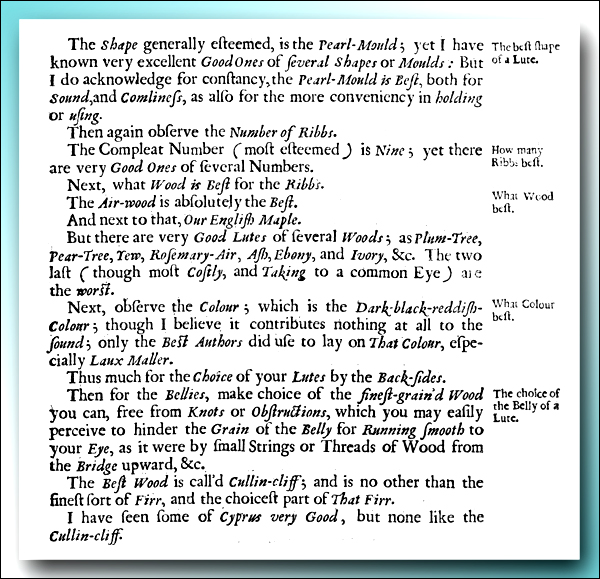

The title-page of Musick's Monument, London 1676. Thomas Mace, writing in The Second, and CIVIL Part: OR The LUTE made Easie of his authoritative book Musick's Monument published in Cambridge and London in 1676, is a treasury of information about the lute of his day; he lists an interesting variety of woods in Chapter III (on page 49) following his recommendations concerning the ideal shape of the lute. We've used his own spelling, italics and capitals in these quotes exactly as the original text presents them on page 49: